Dr. Leslie Biesecker of the National Human Genome Research Institute and Dr. Robert Green of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston recently co-authored guidelines for clinical genetic testing, which were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. These guidelines could help clinicians find a way to make genetic testing affordable and effective.

Dr. Leslie Biesecker of the National Human Genome Research Institute and Dr. Robert Green of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston recently co-authored guidelines for clinical genetic testing, which were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. These guidelines could help clinicians find a way to make genetic testing affordable and effective.

Testing the Exome

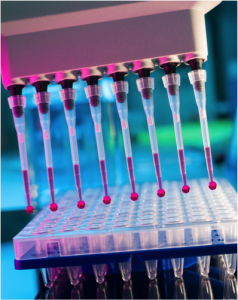

Instead of testing the entire genome, which can be expensive and time-consuming, physicians have learned that exome testing reveals mutations for many different genetic disorders. The exome is the region of DNA that codes proteins, and it makes up about 1.5 percent of a person’s genome.

Dr. Ricki Lewis of CareNet Medical Group, a genetics counselor and author of multiple genetics textbooks, compares the exome to a Wikipedia entry. Like a Wikipedia entry, exome sequencing provides a snapshot of the genome even though it doesn’t convey the richness of the entire picture.

Detect mutations in known genes. Exome sequencing could reveal mutations in known genes after a patient presents with unusual symptoms.

Detect mutations in known genes. Exome sequencing could reveal mutations in known genes after a patient presents with unusual symptoms.- Identify mutations in novel genes. Duke University scientists, in 2012, compared the exomes of 12 children who presented with different combinations of birth defects, intellectual disability and developmental delay. The scientists discovered seven common mutations, two of which were in genes that they’d never associated with the disorders.

- Explain why genetic mutations become disorders in some patients but not in others. A child with a genetic disorder might have a parent who also carries the mutation but who never became ill. Genetic counselors could use exome testing to predict risk for siblings. Also, by understanding how the parent stayed healthy while the child did not, researchers could find new drug targets for disease.

How Exome Sequencing Could Help

Genetic diseases take a heartbreaking toll on individuals, families and communities, affecting people far outside the nuclear family. For example, human services managers (check this page to see if you might be interested in getting a MS in Human Services degree), who put together programs for many people with genetic disorders, often partner with clinicians to explain genetic disorders to patients and their families. The ability to perform exome sequencing in clinics could have significant advantages both for patients and society.

Exome sequencing costs significantly less than whole genome sequencing. In fact, many insurance companies pay for the procedure because being able to prevent disease ultimately costs them less than treating diseases after they happen. So far, exome sequencing has detected genetic variants for a wide range of illnesses including cardiomyopathy, Lou Gehrig’s disease, cancer, epilepsy, Charcot-Marie Tooth disease and several neuropathies.

What Exome Sequencing Cannot Do

When the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced the exome sequencing guidelines, the release pointed out that exome sequencing has its limitations.For example, exome sequencing can find single nucleotide variants, or it can be used for variants in up to 10 sequences. Beyond that, genome sequencing is needed to find longer variations or deletions that could cause genetic disorders.

When the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced the exome sequencing guidelines, the release pointed out that exome sequencing has its limitations.For example, exome sequencing can find single nucleotide variants, or it can be used for variants in up to 10 sequences. Beyond that, genome sequencing is needed to find longer variations or deletions that could cause genetic disorders.

Also, doctors should conduct a thorough family history review before ordering exome sequencing. They should also review the literature to form a basis for ordering the test. Genetic testing can be stressful for patients because the tests might create more questions than answers. Right now, 25 percent of exome tests uncover a disease-causing gene variant, which means that three out of four patients tested will not find answers. Also, the test could find incidental variants that could cause undue burden for the patient.

One Patient’s Success Story

Unfortunately, understanding the genetic story behind an illness doesn’t always result in treatment. Sometimes, it does, and the results are miraculous. In Wisconsin, a team of physicians performed exome sequencing on four-year-old Nicholas Volker, a young boy who developed mysterious holes (fistulas) between his skin and intestines when he ate, causing his intestines to leak into his abdomen. The sequencing identified the variant behind the child’s illness and also detected another genetic mutation, which is usually fatal, that made his body unable to fight off the Epstein-Barr virus.

After a cord blood transplant, Nicholas is able to eat normally, and the fistulas have not returned. Exome sequencing could point the way to similar results for patients of all ages.